Tendon injuries are very common. I have experienced Achilles overuse injury (tendinopathy) myself and from my experience, it can be very frustrating because of the pain it causes when running, jumping and when it gets more severe, simple day to day activities like walking or climbing stairs can be painful. The two common tendon injuries where a lot of the tendon research is based on, is the patella tendon just below the kneecap and the Achilles tendon which inserts into the heel. I think what inspired me to choose this topic was recently when I bumped into my cousin (middle-upper aged man lol!!) who was telling me about his Achilles pain which is getting worse, a typical family member who will listen but not take the advice and continue to complain. I know that many people will develop a tendon overuse injury and it provides a major proportion of our clinical workload.

If you are old enough, you would probably remember these injuries in the 1980’s referred to as ‘tendinitis’ because it was believed that it was the inflammation that was causing the pain. Over time they found that inflammation was absent or small amounts in quantities were present but was not the key factor that was causing the pain and dysfunction. Instead, it was other cells within the tendon matrix that was driving the pathology and causing pain (Cook, Purdam 2009).

The clinical presentation of patients with overuse tendon pain:

|

· Pain after exercise or, the following morning. |

| · Pain-free at rest and becomes more painful when doing an activity. |

| · Pain can disappear when doing an activity and then returns when you have cooled down. |

| · In the early stages, you may be able to train fully but will interfere with the healing process. |

| · There is local tenderness and/or thickening of the tendon. |

|

· Swelling and crepitus (grating, crackling or popping sounds) may be present. |

It is time now to get into the nitty-gritty side of things to explain the biological processes that are taking place within the tendon when pathology exists. Follow me the fellowship…

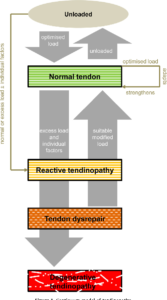

Jill Cook (a professor and a physiotherapy clinician) and Craig Purdam (physiotherapist and worked as a clinician in elite sports) came up with what is known as the Cook-Purdam model to help understand tendon pathology at different stages. The three part classification will be summarised here.

The Cook-Purdam model to help clinicians understand the relationship between loading/unloading and the several stages of tendon pathology.

Stage 1. Reactive tendinopathy

A non- inflammatory response to an acute tensile or compressive overload. This results in a short-term thickening of a portion of the tendon that reduces stress. In another words, the body is clever, it thickens the tendon so it can withstand load. MRI investigations will show mild swelling and greater tendon diameter with minimum disruption to the collagen matrix.

Stage 2. Tendon disrepair

This is when the tendon pathology gets worse and has not been managed properly during stage 1. There is greater collagen matrix breakdown and becomes somewhat disorganised. This is seen clinically in the young who have overloaded tendons (tendons which have not adapted to the demands) but also seen in people across all ages. This stage is difficult to detect clinically from stage1 but obtaining a good thorough history and symptoms can give us clinicians a good idea.

Stage 3. Degenerative tendinopathy

This is the ‘end stage’ of tendon overuse injury and patients can undergo surgery for chronic tendon pain. At this stage the tendon matrix is so disorganised that it cannot repair itself back to a normal tendon (cell death). This pathology exists in the older person, or younger person, or elite athlete with long-term tendon overload. There is swelling and pain (e.g. mid Achilles region). At this stage the tendon can rupture.

Reactive on degenerative tendon

Degenerative tendinopathy can exist in a tendon that has normal tissue. The degenerative part of the tendon can no longer take load when overloaded, so the normal part of the tendon will have to take the load. Overload can produce a reactive change in the normal part of the tendon.

So that is the biology side of things explained and I hope you have understood most of it. In part 2 I will explain how to manage a tendon overuse injury. Stay tuned!!!

References:

Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of loadinduced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2009;43(6):409–16